A Love Affair, with Books

By Tish O'Connor

Born May 15, 1937 in Los Angeles, the third of three children, Dana Levy, my partner in life and work for more than thirty-five years, grew up in San Francisco, which he would always consider his spiritual home, although he lived more of his life in Southern California. He graduated from high school on the Peninsula, then completed two years at San Jose State College, before enrolling for two years of mandatory military service around 1958.

Always artistic, that trait was tapped in Korea, where he served in the peace-keeping mission and first became entranced by Asia. He was assigned to the Army graphics shop in Seoul, and in his second book, Water: A View from Japan (with Bernard Barber, Weatherhill, 1974), he thanks Don Nichols, his supervisor, for teaching him photography, making good use of an overabundance of Army provisions to develop darkroom skills. He joked about his big hush-hush assignment—designing a tombstone for the general’s dog—but, in fact, he gained great experience documenting, creatively, people and landscapes in a fast-changing place foreign to him.

Dana completed his bachelor’s degree at Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles in 1962, then went straight back to Tokyo, which he had visited on R&R, hoping to participate in the planning for the Tokyo Olympics. He held a few different jobs (exhibition design with Fred Harris, a former teacher at Art Center) before landing one with McCann Erikson/Hakuhodo, a joint venture in advertising.

Robert Austin, the author who invited Dana to contribute photographs to the book he was developing on bamboo, was a client of the advertising agency. Robert was generous in allowing Dana’s photography to eventually dominate the project, but Dana’s real break came when he presented comps for Bamboo to publisher Meredith Weatherby, who recognized Dana’s talent for layout, as well as photography, and mentored him through his first book-design process. Weatherhill chose sheet-fed gravure to print the book, giving a rich, velvety tone to the black-and-white images; twenty-five years after it had been issued in 1970, Dana refused to allow the publisher to reissue it in cheaper, but lackluster, offset. Although he subsequently took assignments from McCann in Manila and Sydney, he’d been bitten by the book bug and missed Japan. He angled for a job with Weatherhill and took it, happily returning to Tokyo in 1972.

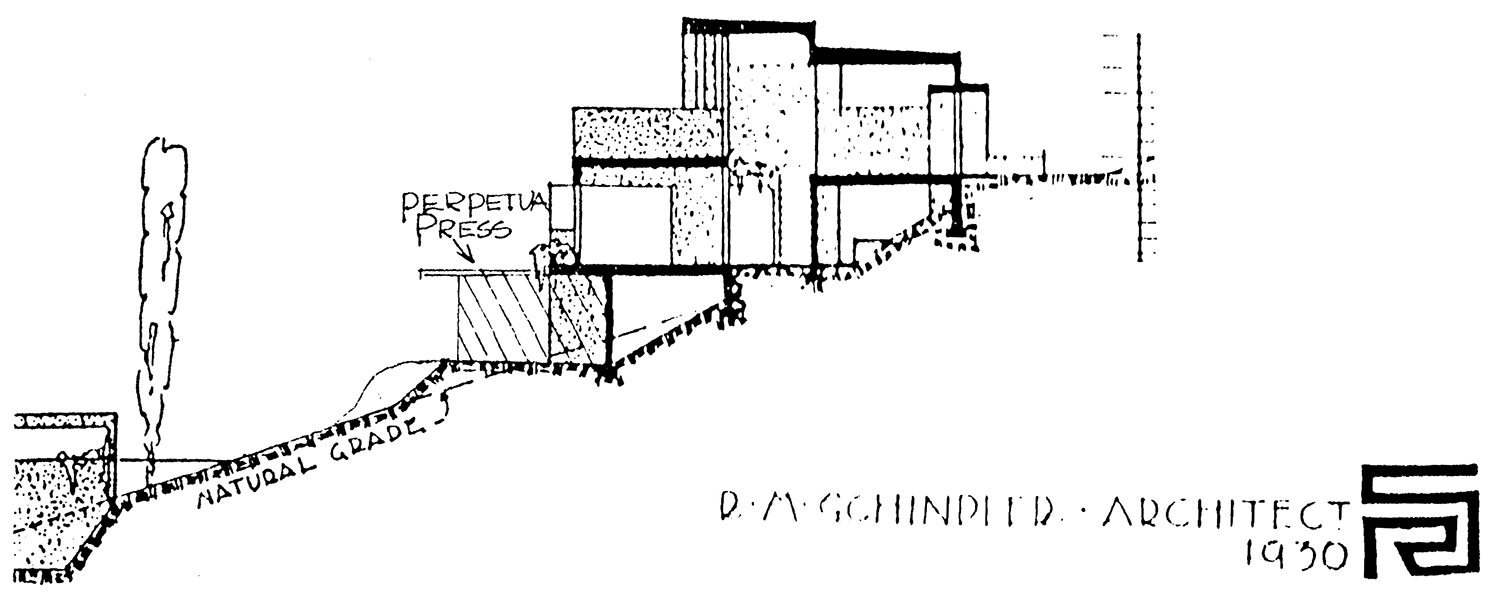

By 1976 Dana was living in New York City, renovating raw space on Thirteenth Street into a live-work loft and developing the mix of publishing clients that would persist throughout his life. Dana and I met in the offices of George Braziller, where I had been hired as an editor of art books and recognized that he, like Braziller, had an innate love for books that I wanted to understand. Sharing a passion not only for the final book, but for the process of creating it, drew us together. That process of recognizing something of value—beautiful, important, or true—and creating a book that expressed those same values sustained us, and Perpetua Press, for thirty years.

As Dana had been mentored by Meredith Weatherby, I found my guiding spirit in George Braziller, who combined a genuine appreciation for art with a respect for scholarship, and followed his instincts to publish an eclectic, wonderful collection of books. The crucible of fire from which Dana and I emerged as publishing partners was a collaboration among Phillip Guston and his dealer, David McKee, Henry Hopkins, director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and his then-assistant, curator Karen Tsujimoto, the Los Angeles print studio Gemini GEL, writer Ross Feld, and Braziller that documented a retrospective exhibition of the abstract expressionist, which opened two weeks before his death. It was as complex as the previous sentence and a model for the productive interaction of Perpetua Press with its clients.

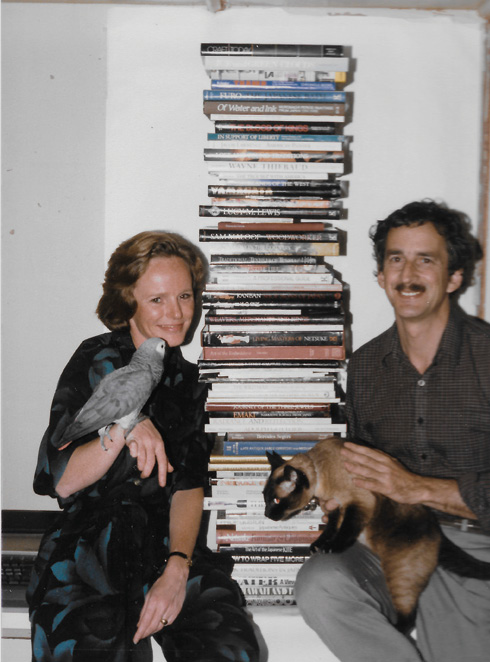

Dana won the American Book Award in 1980, when the categories in non-fiction were expanded to include illustrated books, for Anatomy Illustrated (with Emily Blair Chewning), published in original paperback by Simon & Schuster—which were the names he chose for his pets, an African gray parrot and Siamese cat. The prize was a Louise Nevelson sculpture that has hung prominently thereafter in our home.

Among Dana’s New York clients was Kodansha International, the other Japanese publisher of English-language books about Asia, which asked him to evaluate materials that George Nakashima had assembled for a book about his work. Dana volunteered to supplement the photography, which entailed several visits to the furniture designer’s workshop in New Hope, Pennsylvania. That project initiated an award-winning series on American crafts, which eventually included the woodworker Sam Maloof, as well as ceramists Lucy Lewis, Pete Voulkos, and Warren MacKenzie.

The adventure of working together continued with an extraordinary introduction to Japan where I accompanied Dana on a search for kanban (traditional shop signs) and to visit Japanese hot springs. One focus was the book that would become Furo (with Peter Grilli). The other was Dana’s sole opportunity to be a curator, selecting early commercial graphics for an exhibition sponsored by Japan Society in New York and Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. He was enthralled by the process of developing a graphic idea in three dimensions, visualizing objects not just on the page, but hanging in a gallery. Dana was also proud that the exhibition catalog was issued both in English and translated into Japanese by Weatherhill (1983), and later, by Chronicle Books in a paperback edition, Kanban: The Art of the Japanese Shop Sign, that emphasized the graphics, rather than the ethnography, of those objects.

In 1982 we moved to Los Angeles, where I had accepted a job managing the publications department at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and specifically documenting LACMA’s Olympic Arts Festival exhibition. When the staff designer got pregnant and was unable to complete that job, the best book designers in Los Angeles were asked to submit their portfolios for review. Although my boss announced that Dana could not be considered, at my insistence, his samples were included. The museum’s director chose Dana to design A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, confirming what I already knew: Dana’s design was peerless in any context. Although my boss announced that Dana could not be considered, at my insistence, his samples were included. The museum’s director chose Dana to design A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, confirming what I already knew: Dana’s design was peerless in any context.

Recognizing that museums were becoming publishers but often lacked professional staff in key areas, we started Perpetua Press in 1984. Our clients included many local museums in Los Angeles: the Autry, Huntington, Getty, Natural History, Pacific Asia, and Skirball. Dana’s affiliation with Japan seemed to make him a natural choice when the subject was Asian art, and led to his first big job for the National Gallery of Art—Japan: The Shaping of Daimyo Culture—as well as many books for the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

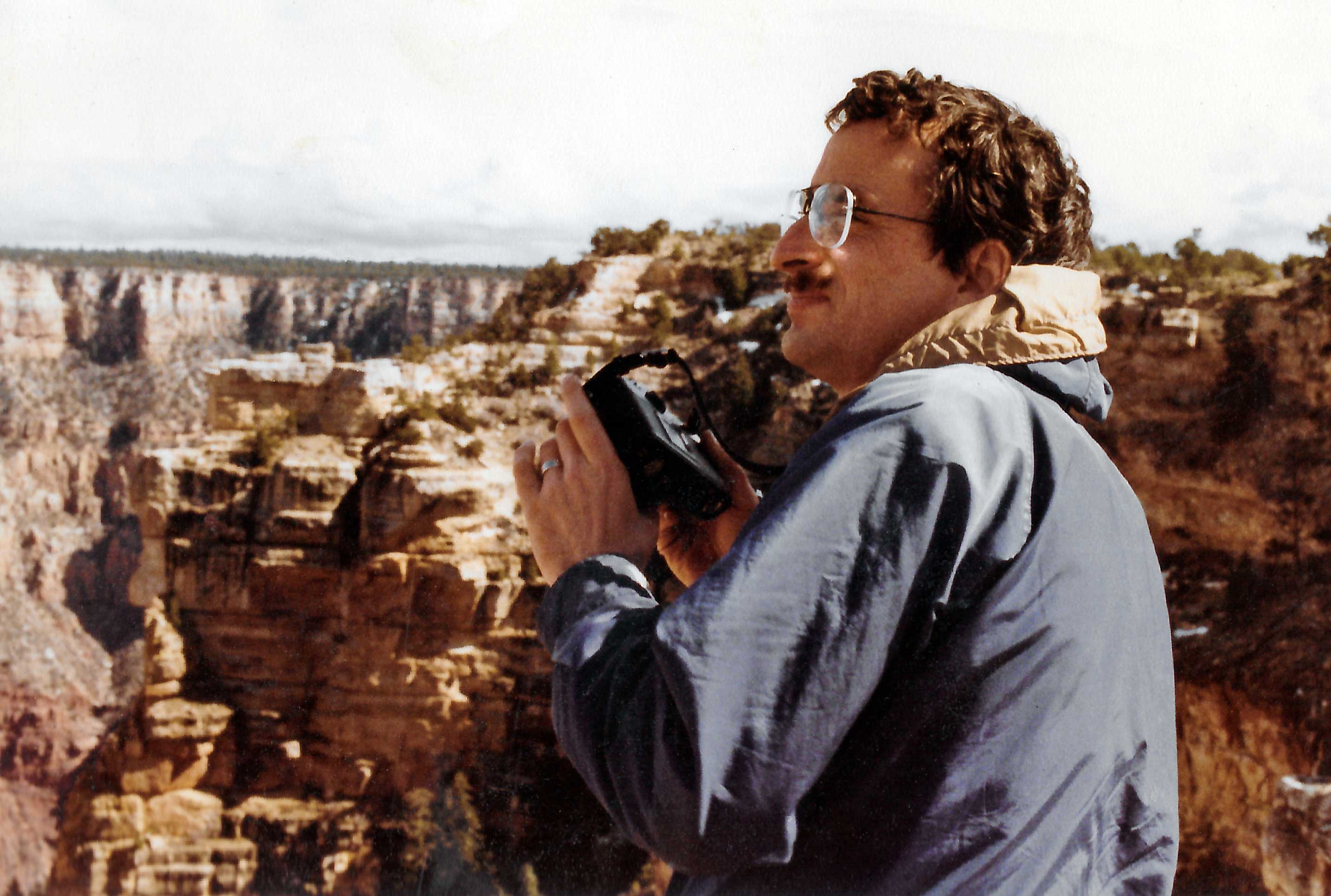

Perpetua Press produced books for various branches of the Smithsonian, and especially enjoyed meeting challenges posed by Bill Fitzhugh, director of its Arctic Studies Center. We worked with museums across the US, from the Harvard Art Museums to the Honolulu Academy of Arts, and enjoyed a fruitful collaboration with the University of Washington Press and its long-time publisher, Don Ellegood, helping establish it as a major distributor of museum publications. Among the projects we most enjoyed was developing a series of large-format nature photography books for publisher Hugh Levin, exploring the Grand Canyon, National Parks, Alaska, Hawai‘i, Yellowstone and the Grand Tetons, among other “spectacular” locations.

Our work at Perpetua Press was a continuing education that allowed us to share in the passions and research of many talented scholars and curators, artists and writers. The legacy of that creative collaboration will endure in the books we produced, including those illustrated on this website. If they inspire others to explore and seek to understand the complexity and brilliance of this world, that will be the most fitting tribute to Dana’s life and work.

Dana and I focused on our professional lives until we decided to have a child—and then we engaged the gods and our friends and family in a fertility rite and got married on December 28, 1991, after twelve years together. Our son Conor was born nine months and two days after our wedding. In fatherhood, Dana found a new source of inspiration and satisfaction. We moved to Santa Barbara in 2001, for its good public schools and the natural beauty of this place that comforted Dana at the end of his life.

Dana Levy died on March 8, 2017, two months short of his eightieth birthday, of non-Hodgkins lymphoma, which he had battled successfully (with two years of chemotherapy) after his initial diagnosis in spring 2009.

|